My Experience with Pseudoscience

UPDATE on 18/06/2025: I've written

a blog-post about how I recently left three groups that often engage

in cult-like reasoning.

UPDATE on 04/02/2024: I have made a video refuting the Flat-Earth theory as a former Flat-Earther. In case your browser cannot open it, download this MP4 and open it in VLC or something similar. And please spread the word, Flat-Earthers need to be woken up.

UPDATE on 03/10/2021: I have received some criticism on Internet forums that this text appears to be intended to slam everybody else as pseudoscience except me, and that it is what pseudoscientists do. That was not my intention at all, my intention was to make you more skeptical of all things outside the mainstream, including me. As well as the ideas you come up with that contradict the mainstream science. Outside of scientific consensus, no idea is anything more than possibly right. I, for example, think my idea about collision entropy of different parts of the grammar being measurable and useful to prove some etymologies of names of places in Croatia (you can read an English-language summary on my blog) has enough probability to be right to be worth sharing, and that it is at least interesting even if it is not correct. I am quite certain that, even if I am misunderstanding statistics here, my misunderstanding is not nearly as severe as that of anti-vaxxers or typical pseudolinguists. To judge whether it is correct, use your brain, you are probably more objective than I am. But also have a bit of self-doubt and realize there are people who know far more than you do about the subject, and who are far more likely to be right. Understand also that it is sometimes hard to tell who is an expert in some field (physicians, for example, know about nutritional science only slightly more than an average person), or even if anybody has meaningful expertise about the topic (for example, what happens if we try to radically transform the society to deal with climate change or a pandemic). And try to make sure you are hearing both sides of the story, and not just one which is easier to read (which is usually pseudoscience). (UPDATE on 04/09/2025: Anyway, it seems to me that I was doing an error in my calculations, not so much because of misunderstanding statistics, but because of ignoring linguistic typology and cross-linguistic phonology. Namely, I implicitly made the assumption in my calculation that the collision entropy of the pairs of consonants is approximately-evenly distributed among the pairs of consonants in a word. That is approximately true for languages such as Hawaiian, with very restrictive phonotactics, but is not remotely true for languages such as English or Croatian. English and Croatian allow for many consonant clusters at the beginning and at the end of the word, and those consonant clusters are governed to a large extent by the Law of Sonority, also known as Sonority Sequencing Principle. The Law of Sonority effectively, in languages with lenient phonotactics such as English or Croatian, decreases the collision entropy of word-initial and word-final consonant pairs by around 1 bit. That makes my calculations wildly off. For example, the upper bound of the p-value of the k-r pattern in the Croatian river names is not 1/17, but is around 85%. You can read more about it on my blog-post about leaving cults. Two things are really amazing to me from this story. One is that the biggest problem by my calculation wasn't noticed by some expert in Croatian toponyms, with whom I was discussing my paper for three long years, but by some Semitic languages expert on Discord. And the second thing that's amazing to me is that it took me nine years to realize what is obvious to most laymen: that there is no good way to scientifically study ancient toponyms. It took me 5 years of studying toponyms to realize that the mainstream methodology, the Mayer's one, does not even work on paper, and it took me 4 more years of studying to realize that the main opposing methodology, the Krahe's one, works on paper but not in reality. It is not obvious to me, as a computer engineer, what would be the mathematical justification for the Mayer's methodology, and the Krahe's methodology appears to be justified by basic information theory, but, once you look more into it, you see that natural languages do not really behave the way basic information theory predicts. How it is that many people were able to see that a lot sooner than I was? It's not as if the study of the toponyms involves a conspiracy theory or is based on endless not-even-wrong arguments, and the lack of significant scientific consensus, while real in the study of the toponyms, is not at all obvious at the first sight. And the ad-hoc hypotheses, if existent in the study of toponyms, are not at all blatant. I fail to see why the study of the toponyms would be ad-hoc if chemistry is not ad-hoc, for example. Many people are saying "Math - that's the difference between science and bullshit.", but the study of the toponyms is not a completely math-free field. Especially not my paper in which my main argument was that basic information theory suggests that the p-value of a certain pattern in the Croatian river names is between 1/300 and 1/17. Furthermore, it seems undeniable to me that people, with the possible exception of my professors at the university, were more skeptical of my work the more math I used in my arguments, rather than becoming less skeptical. So, how were so many people capable of almost-immediately realizing that's bullshit? I'd love to hear your thoughts.)

Pseudoscience simply means "false science", something which is presented as science, but demonstrably doesn't follow the methods of science. Many people believe that pseudoscience is basically isolated to specific and widely discredited fields, like astrology and numerology. However, I would argue that pseudoscience is probably everywhere,

Do you know how,

for example,

the mathematicians

know the Pythagorean

Theorem is correct?

In school,

we aren't taught

how scientists

know what they know.

at least wherever there are some people fighting for the truth (because

at least some of them will be too ignorant for that).

Pseudosciences are widespread because of the way people react to nonsense: they ascribe the apparent incoherence to their own lack of knowledge. And more intelligent you are, more likely you are to fall into that trap, because, more intelligent somebody is, easier it is for him to imagine that there is something he is unaware of, so that something that doesn't make sense to him actually does make sense. This type of thinking is as flawed as it can get, but it's very common (and perhaps mostly subconscious).

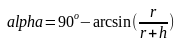

The second statement is false, because, well, the basic trigonometry. First of all, if the Earth were flat, I hope you agree, there would be no horizon in the first place for us to make this observation. Therefore, simply yelling that the Earth is flat isn't an explanation at all. Of course, those who claim the Earth is flat will claim there is some basically undetectable (for whatever reason) curving of light upwards, and that also can't be considered an explanation.

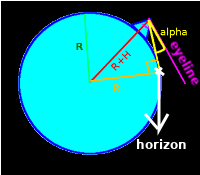

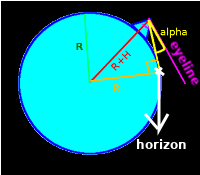

A diagram explaining

why the horizon

appearing to rise

as we climb doesn't

prove the Earth

is flat

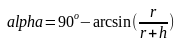

Second, if you draw a diagram, you will see that the angle at which you

see the horizon is given by the formula (assuming the Earth is a perfect

sphere, which it actually isn't, but that's not so important here)

, where r is the radius of the Earth (around 6'000'000 meters)

and h is your height relative to the surface of the Earth. So, if

you are on the Mount Everest (9'000 meters height), you will see the

horizon at the angle of 3.14 degrees. Barely perceptible. Actually, it's

not even barely perceptible, because, when you are on the Mount Everest,

the mountains hide the horizon in the first place. Furthermore, some

optical illusions make it clear that what our brain perceives to be eye

level, or even what it perceives to be a horizontal level at all, is

determined not only by the equilibrium sense in our ears, but also by

visual clues. This is well-known to mountain cyclists as the false flat

illusion. That makes the difference between eye level and the horizon

even more difficult to perceive. The fact that the horizon is not always

at your eye level, however, can be seen in at least two ways. You can

see it indirectly by watching the sunset sitting down and then quickly

standing up (the sun stays at your eye level as you stand up, but the

horizon falls slightly). And you can also see it directly using a device

with a gyroscope and a camera (such as modern smartphones). I think the

fact that the horizon demonstrably falls as you climb is a good argument

against the Earth being flat, you can see on

this forum thread

whether it works.

, where r is the radius of the Earth (around 6'000'000 meters)

and h is your height relative to the surface of the Earth. So, if

you are on the Mount Everest (9'000 meters height), you will see the

horizon at the angle of 3.14 degrees. Barely perceptible. Actually, it's

not even barely perceptible, because, when you are on the Mount Everest,

the mountains hide the horizon in the first place. Furthermore, some

optical illusions make it clear that what our brain perceives to be eye

level, or even what it perceives to be a horizontal level at all, is

determined not only by the equilibrium sense in our ears, but also by

visual clues. This is well-known to mountain cyclists as the false flat

illusion. That makes the difference between eye level and the horizon

even more difficult to perceive. The fact that the horizon is not always

at your eye level, however, can be seen in at least two ways. You can

see it indirectly by watching the sunset sitting down and then quickly

standing up (the sun stays at your eye level as you stand up, but the

horizon falls slightly). And you can also see it directly using a device

with a gyroscope and a camera (such as modern smartphones). I think the

fact that the horizon demonstrably falls as you climb is a good argument

against the Earth being flat, you can see on

this forum thread

whether it works.

The third statement is wrong, because, well, the word *vīlla (with a long 'i'), borrowed into Old Croatian, would give something like *Bȁo (with a short falling tone on 'a') in Modern Croatian. Even if a linguist doesn't know the sound changes that happened between Old Croatian and Modern Croatian, he still wouldn't have expected the word to remain unchanged for more than a thousand years. The consonants, the vowels and the accent "matching perfectly" (ignoring the sound changes that have occured) is a strong (though not a necessary) argument for the words being unrelated, rather than related, because the sound changes don't affect individual words, but whole languages. A failure of a sound change to affect a word it could have affected is what requires an explanation, and not the word changing to the unrecognizability due to the regular sound changes. A good response to somebody who is suggesting such etymologies on an Internet forum might be something along the lines of:

The point is, it's very easy for a layman to convince himself those statements (and the similar ones) make sense, sometimes even easier than it is to understand the true science to the point when it actually makes sense. Our senses are unreliable. We witness illusions and hallucinations (at least the ones such as dreams) all the time. Even when they do give us correct information, it's very easy to misinterpret. The science seeks to correct those things. Pseudoscientists sometimes appear to exploit those things to make people believe absurdities.

What we are taught at school might even have a detrimental effect to our ability to detect pseudoscience not only because they make us more susceptible to the survivorship bias, but also because schools often make us think we have competences we don't. The schools make us think we know how science works, but we are, thanks to the schools, not only ignorant, but also have a wrong conception about it. We are, for example, being taught linguistics and philology all the time in our Croatian language classes, and most of the people think that linguists and philologists are people who like to use some confusing arguments to discuss what is grammatical or stylistically right to say and what isn't. Nothing could be further from the truth, linguists and philologists are people whose job is to make testable theories about how languages work. But, if we think that linguists and philologists don't make testable theories, we see no reason to believe what they say about languages. And the same goes for most of the other sciences we are supposedly being taught at school.

Furthermore, because schools do not teach about the most dangerous pseudoscience in history that is Lysenkoism, the rhetorics from global warming deniers or anti-nuclear people such as "CO2 is plant food. The effects of increased CO2 levels in the atmosphere may very well be positive." or "Nuclear energy is too expensive. I would much rather protect people from the real danger of energy poverty than from the hypothetical dangers of global warming." sound, well, normal to most of the people. In reality, they should remind us of Lysenkoism, the time in not-so-distant past when people tried conquering the nature they did not understand instead of seeking to minimize their impact on nature, and caused massive crop failing and famine. Those rhetorics should sound insanely irresponsible. Only slightly less irresponsible than the suggestions that we should continue massively using antibiotics in the egg industry (as the result of that is completely predictable, unlike what a massive increase in CO2 levels in the atmosphere might do). But people, because they are unaware of Lysenkoism, usually fail to see that.

It is also important to understand that the school curriculum contains some half-truths, things that are technically true, but can easily mislead people. A good example of that, in our biology classes we are told that the synthesis of every protein begins with methionine, and that no protein can be synthesized without methionine. That is technically true, but telling students that without telling them that too much methionine raises the cholesterol levels is... dangerous, I don't know which other word to use here. It can easily mislead students into thinking a diet high in methionine is healthy, which it is not. Or, in our IT classes, we are taught that antivirus programs protect us from malware. But what we are not taught is that antivirus programs have false positives (detecting innocent programs as malware), the consequences of which can be just as bad as the actual malware. Students are being misled to think antivirus programs help us significantly, when it is questionable whether they help us at all.

And I think what schools teach about programming is one giant half-truth. Those programming competitions encourage students to study useless or even harmful things (superficial understanding of as many data structures and algorithms as possible, short variable names and other things that help you write short programs fast...). I have written a lot about it at the beginning on my Informatics page.

UPDATE on 07/01/2026: Another example of a potentially-dangerous half-truth taught in school. In our 9th-grade biology classes, we are taught that Vitamin K is necessary for the osteoblasts to extract the calcium from your blood in order to store them into the bone's calcium-II-phosphate. And we are also taught that very low levels of Vitamin K cause heart attacks. I am sure quite a few students misunderstand it or even misremember it as if it is written in our textbook that Vitamin K decreases the risk of heart attacks because it makes osteoblasts extract calcium from your blood into the bones. Which is totally false. Calcium in your blood is basically never the limiting factor in calcifying your cholesterol: there is always too much of it for the exact amount to matter. Vitamin K works to prevent heart attacks by enabling the production of the enzyme called Matrix GLA Protein, which decalcifies the cholesterol, however, taking megadoses of Vitamin K does not make your body produce more of the Matrix GLA Protein. And thinking Vitamin K prevents heart attacks by lowering the amount of calcium in your blood is a dangerous misconception because it makes wrong advices like "Don't worry about saturated fat or trans fat you eat, just eat enough vegetables to get enough Vitamin K, and you should probably avoid calcium-rich foods such as orange juice." seem scientifically plausible. I've made a YouTube video about that (MP4).

It is important to understand that, while censorship might indeed make it more difficult for conspiracy theories and other pseudosciences to spread, it also prevents them from being discussed. For example, Tony Heller is a blogger supporting all kinds of conspiracy theories, including that the elections in the US are fake (presumably implying elections all around the world are fake and that democracy is useless). He made a YouTube video full of long-debunked arguments for the 2020 US election being fake (many of them repeated from the previous elections). I made a video debunking his arguments once again, in hope to wake up some people who truly believe that. However, YouTube wouldn't allow me to upload it, presumably due to some censorship filter. So I uploaded it on GitHub, where I will arguably have less audience. Clearly, censorship by YouTube has really hurt me more than it has hurt Tony Heller.

It is also important to understand that censorship on the Internet pushes people who hold extreme beliefs into darker and darker corners of the Internet, where they are far less likely to hear the other side of the story.

I also think the problem of global warming is given too much attention to by the mainstream media, at least compared to other global problems. Even though extensive farming of cows emits 3 times (UPDATE: OK, I am not sure any more this statistic is accurate. I've written about that on my other blog-post. Still, it's indisputable fact that grass-fed cows emit more methane than grain-fed cows, even if the difference is not 300%.) as much methane per kilogram of meat than factory farming does (because cows emit a lot of methane when digesting grass, but very little methane when digesting grain), it is almost certainly better than factory farming which leads to superbacteria (not to mention animal rights issues regarding factory farming). I think mainstream media focusing too much on global warming, while ignoring other global issues, makes people blind to those things.

If there was a direct connection between what's happening in reality and what the media are saying, we'd expect the media in the post-pandemic world to constantly be yelling "If you want to do the number one thing that's going to decrease the chance of a new pandemic happening within our lifetimes, then you should either stop eating eggs or make sure that the eggs you are eating don't come from factory farms. There is little or nothing we can do about virus pandemics, but there is something we can do about superbacteria. Around 70% of antibiotics these days is being used by the egg industry.". Yet, that's not happening. What is going on here? Lobbying by the egg industry? That's a simple explanation, but I think it is wrong. First of all, egg industry obviously isn't lobbying alternative media, which also tend to not to talk about superbacteria. Alternative media is getting its content from the mainstream media. Bloggers are often making responses to the claims made by the mainstream media, so if the mainstream media is detached from reality, chances are, alternative media will be as well. I think that what's going on here is that media, both the mainstream and the alternative media, is covering activists a lot, and activists tend to choose complicated problems such as global warming, rather than relatively simple problems such as superbacteria. That's unfortunate, and I've written a blog-post about that.

Everyone has to learn to recognize pseudoscience by themselves. What actually helps is knowing how people discover the pseudoscientific "knowledge".

UPDATE on 14/05/2025: You know, a hidden premise here, I think now, is that everybody can be brought to reason, and that debate is a cure for irrationality. But is that true? I am not sure. Let's think about Flat-Earthism. A Flat-Earther who uses the argument "Why don't the sunrays appear parallel as they pass through the clouds?" probably can be brought to reason with a simple discussion: he is merely misunderstanding psychophysics (perspective). But a Flat-Earther who uses the arguments such as "Why does the horizon appear to rise with us as we climb?" (like I was using back when I was a Flat-Earther), it's going to be quite a bit more difficult. He is not only misunderstanding psychophysics, he is also not accepting the basics of scientific methodology: he is trying to replace a theory which explains at least something with a theory that explains precisely nothing. Flat-Earth Theory does explain the sunrays appearing to converge (by asserting that the Sun is merely 5'000 kilometers up in the sky), but it does not explain the horizon appearing to rise with us as we climb. Furthermore, many, if not most, Flat-Earthers use arguments such as "Look out through the window!". Attempting to reason with somebody who uses such arguments is probably futile. And I think the proponents of mainstream interpretation of the names of places in Croatia are somewhere between the second and the third group. They are following a methodology, it's just that their methodology has no apparent mathematical basis (and, in fact, appears to go precisely against mathematics). They are convinced that etymologies from languages we know a lot about (Croatian, Latin, Celtic...) are for some reason more probable than etymologies from languages we know little about (Illyrian...). That's why they will insist that the river name Karašica is related to Latin fish name carassius (or, more serious proponents of mainstream linguistics might insist that it comes from Turkic *karasub meaning "black water"), and that that's a lot more probable than my suggestion that Karašica comes from Illyrian *Kurr-urr-issia (flow-water-suffix). And they cannot articulate why they think that (other than perhaps by giving the pathetic reason "Well, that's the type of reasoning present in many papers about etymology published in peer-reviewed journals."). You can try to explain to them that their methodology seems to go precisely against the basic information theory, that the basic information theory (Birthday Paradox and Collision Entropy) strongly suggests that the p-value of that k-r pattern in the Croatian river names (Krka, Korana, Krapina, Krbavica, Kravarščica, and two rivers named Karašica) is somewhere between 1/300 and 1/17... but that doesn't convince them. They will rather trust "traditional methods" than mathematics. Is attempting to reason with people who think that way worth it? Is it even possible? You be the judge. Maybe my theories are wrong. Maybe there is some technical detail in the field that touches both information theory and linguistics that makes my calculations misleading. But attempting to debate with most proponents of mainstream linguistics is ineffective if not counter-productive as an attempt to figure that out.

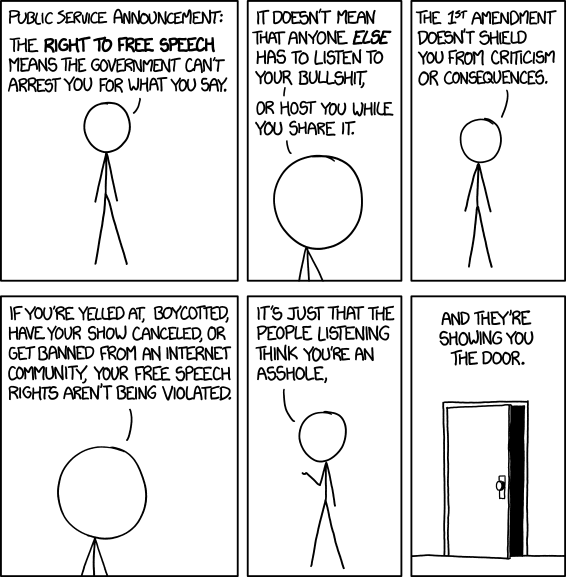

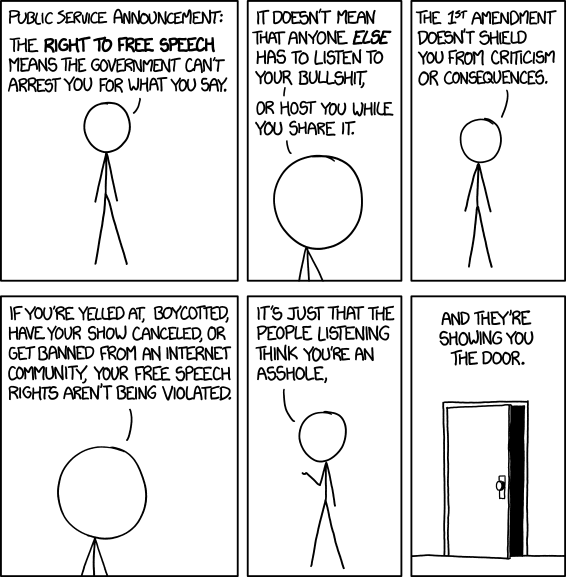

UPDATE on 18/08/2025: You know, the number one argument that liberals give for the notion that censorship by private companies is somehow justified is: "The government has no duty to enable you to speak things most people disagree with. The term 'free speech' only means that the government itself cannot punish you for saying outrageous things, not that it should enable you to do that. The 1st Amendment of the US Constitution begins with: 'Congress shall pass no law...'.". Here is an XKCD comic illustrating that point: Well, I don't think many people actually believe that, although they say

that. "The government has no duty to enable people to speak."? Excuse me, but what about the laws that are necessary for the

Internet as we know it to work? For example, the laws against open DNS

servers (without which the Internet as we know it would almost certainly

be paralyzed by DNS reflection attacks)? I think that everybody who is

not a radical anarchist would agree that those are necessary laws, and

that the government has duty to pass and enforce such laws. But, then,

why stop there? I've asked

a Quora question about this point.

Well, I don't think many people actually believe that, although they say

that. "The government has no duty to enable people to speak."? Excuse me, but what about the laws that are necessary for the

Internet as we know it to work? For example, the laws against open DNS

servers (without which the Internet as we know it would almost certainly

be paralyzed by DNS reflection attacks)? I think that everybody who is

not a radical anarchist would agree that those are necessary laws, and

that the government has duty to pass and enforce such laws. But, then,

why stop there? I've asked

a Quora question about this point.

Pseudoscientists do what's called ad-hoc hypotheses. An excellent example of that is given by Carl Sagan. Suppose somebody claims they have a dragon in their garage. Of course, you don't believe them and ask them to show it to you. He says it's invisible. You ask him to spray some color on it to make it visible. He says that won't work because the dragon in his garage is incorporeal. So, you ask him to try to measure the temperature of the fire in its mouth. He says that won't work either and that the dragon's fire is heatless. I've studied many pseudosciences, and I can safely tell you, once you get deeper into some pseudoscience, that's the type of reasoning you engage in. You don't want to do an experiment because you know what the result would be. Scientists honestly try to falsify their hypotheses by experiments or observation. Pseudoscientists try to make up reasons why an experiment wouldn't work. You know, the horoscopes don't work because making one is error-prone. If you see such type of reasoning again and again in some field, you can be certain you are dealing with a pseudoscience.

You need to understand that, if you are going to deal with empirical matters, you will sometimes have to apply the Occam's Razor and reject the models that are full of ad-hoc hypotheses. Because almost every empirical claim can be defended using ad-hoc hypotheses, even the claim that the Earth is flat. Either you are going to be a radical skeptic (thinking knowledge is impossible) or you are going to sometimes be applying the Occam's Razor.

That's not to say the proponents of mainstream science sometimes aren't doing ad-hoc hypotheses. For instance, when I went to discuss the paper about applying informatics to the Croatian toponyms I published in Valpovački Godišnjak and Regionalne Studije (you have an English summary on my web-page about toponyms) on Internet forums, one of the first responses I got is "Maybe the collision entropy of the nouns in the Croatian language is significantly lower than the collision entropy of the entire Aspell word-list. Have you checked for that?". That's, if you ask me, a blatant ad-hoc hypothesis: it is inventing the reason why an experiment wouldn't work. And it's not on me to do some much more complicated experiment (somehow compile a list of nouns in the Croatian language) because of somebody's ad-hoc hypothesis.

One of the most unfortunate things about science is that, the more science advances, the easier it is for pseudoscientists to make ad-hoc hypotheses that sound plausible to a layman. For instance, in ancient and medieval times, Flat-Earhters probably couldn't have thought of explaining away the distance-between-far-away-places problem by claiming we are living in a non-Euclidean space: the concept of a non-Euclidean space wasn't known then. Moon deniers most likely didn't exist in ancient times for the simple reason that holograms didn't exist back then for somebody to claim that the Moon is a hologram. And if the Swahili grammar wasn't well-known, somebody couldn't comment on my paper "Your experiment isn't taking into account the possibility that nouns in the Croatian language have a significantly lower collision entropy than the rest of the words in the Aspell word-list." without sounding insane.

So, why do many people on Internet forums rather trust ad-hoc hypotheses than those following the scientific method? I think that two things play a role.

Number one, ad-hoc hypotheses often sound, as Croatians would say, more "domišljato" (I don't know if there is an English word for that). Saying that we are living in some kind of a non-Euclidean space sounds more "domišljato" than saying that the Earth is round. Saying that the nouns in the Croatian language somehow magically (I can see how that might be the case in Swahili, but I fail to see how it could be the case in the Croatian language) have a significantly lower collision entropy than the rest of the words in the Aspell word-list sounds more "domišljato" than suggesting that that k-r that repeats in the Croatian river names was the Illyrian word for "to flow". I think that many people are looking for what sounds more "domišljato" instead of trying to apply the Occam's razor.

Number two, I think many people don't realize that ad-hoc hypotheses are actually a more complicated explanation. Back when I was a Flat-Earther, I thought that ships disappearing bottom first was an illusion caused by waves. I didn't try to calculate how big waves would have to be to hide a ship that's 5 kilometers away, to realize that, unless there is something weird going on with light, those waves would have to be higher than your eye-level. Back when I was a Flat-Earther, I thought that different constellations being visible from different places on Earth was caused by the stars being 3'100 miles up in the sky. I didn't realize that would, unless there is something weird going on with the light, cause constallations to have different apparent shapes depending on where you look at them from. And so on. If you disregard quantitative methods, you will have trouble telling apart reasonable explanations from ad-hoc hypotheses.

However, sometimes I ask myself, are the beliefs I hold pseudosciences based on that? About Digital Physics, the two most notable proponents of it are Gerard 't Hooft and Stephen Wolfram. What do they agree on? Actually, very little. Gerard 't Hooft thinks the universe is a type of a computer known as cellular automaton, so that there is locality in it. Stephen Wolfram argues the universe is very unlikely to be cellular automaton, because that makes phenomena such as Quantum Entanglement very difficult to explain, and he thinks the universe is a Turing Machine. I agree with Stephen Wolfram, but that is only because I am able to understand his arguments, while I am not able to even understand Gerard 't Hooft's arguments. What's obvious is that there is little or no scientific consensus among the proponents of Digital Physics. I am not sure how proponents of Digital Physics would respond to this argument "If Digital Physics is true, why aren't you able to agree on what type of a computer this universe is?". About Libertarianism, the two most notable proponents of it are Milton Friedman and Noam Chomsky. But they have wildly different views on how the economy would actually work in a libertarian society. Is that a sign that Libertarianism is pseudoscience? Proponents of Libertarianism argue that it is not, and that this is because Libertarianism is not an authoritarian ideology. Namely, they argue proponents of authoritarian ideologies are able to give you detailed description of how the economy would work if their ideology was implemented and even what happens in case of some catastrophy, while non-authoritarian ideologies are not. That is why non-authoritarian ideologues are not able to agree on the details of how society will function without a government. You be the judge whether that makes sense. In my alternative interpretation of the names of places in Croatia, I am going strongly against the scientific consensus. There is a virtual consensus among the people who study names of places in Croatia that names of places prove that Illyrian belonged to the satem group of Indo-European languages. I think (if you cannot open that link, try this) that there is only one scientifically rigorous argument (by scientifically rigorous argument I mean an argument with a p-value) one can make about whether Illyrian was centum or satem, and that it argues for Illyrian being a centum language. Am I being a pseudoscientist here? You be the judge.

Another example of a lack of a scientific consensus is this. Croatian toponyms show sound changes that are, to quote the StackExchange user Janus Bahs Jacquet, "At first blush, this looks very unexpected [to somebody who knows the basics of Slavic historical phonology].". For example, we see empirically that 'o' in ancient Croatian toponyms sometimes gets reflected in modern Croatian toponyms as 'i' (the Illyrian suffix "-ona" regularly gets reflected as "-in"), sometimes as 'u' and it sometimes disappears entirely (and, apparently, it never gets reflected as 'o'). But why? You can read the Janus Bahs Jacquet's explanation at the end of his answer to one of my forum questions. And you can read my explanation. And you can read the explanation in the Dubravka Ivšić'es PhD thesis. So, we have three different explanations of what actually happened. Are we doing pseudoscience here? You be the judge.

Sometimes I ask myself if the study of the Croatian toponyms is a pseudoscience because of that. The proponents of mainstream onomastics constantly demand a more complicated experiment to prove that the k-r pattern in the Croatian river names is statistically significant, but they never do an experiment to suggest that it isn't..

On the Flat Earth Society forums, many Round-Earthers make weak or even outright wrong arguments, such as "If the Earth is accelerating towards me when I jump, why do I feel like I'm being pulled downwards?" or "Why hasn't the Earth reached the speed of light yet?", which are misunderstandings of special relativity. The argument "How it is that the gravitational acceleration (approximately 9.8 m/s2) measurably changes if you climb on a high mountain?" is correct (in fact, there seems to be no way a Flat-Earther can explain that without contradicting many laws of physics), but it is unlikely to be convincing. Many people on the Flat Earth Society forums are making this argument: "How it is that you can see completely different stars at the same time if you look from the South Pole and from the North Pole?". In fact, that's trivially explained if you assume the Earth is flat: simply suppose stars are close to Earth. What's not easy to explain if you assume the Earth is flat is that if you look at the night sky from two points on Earth relatively near each other, you can see different constellations, but the common constellations (visible from both points) have the same apparent shape. If the stars were close, we would expect them to have different apparent shapes due to perspective distortions. Many people on the Flat Earth Society forums are making the following argument: "If the Earth is flat, how it is that birds appear to fly at a lower and lower altitude as they move from the zenith to the horizon?", which is a blatant misunderstanding of the perspective. There are many good perspective-based arguments for the Earth being round, but this is not one of them. And so on.

Furthermore, in my experience, many people on Internet forums are making good arguments, but are incapable of presenting those arguments properly. Many people who want to refute Flat-Earthism say GPS relies on the Earth being round, but, when asked how exactly, they give some incomprehensible word-salad. In fact, GPS is a good argument against the Earth being flat, because, if the Earth was flat and GPS was land-based, GPS devices wouldn't be able to tell their location with only three signals. When you know your distance from three locations, you can calculate two points where you might be. Now, if the Earth is round and GPS devices know they are below the satellites they are receiving the signals from, they can elliminate the point that's above the satellites. But if the Earth is flat, three signals would not be enough to tell your location, because how could GPS devices possibly know if they are above or below the emitters? But people on Internet forums tend to be unable to present that argument in such a comprehensible way. Similarly, when trying to refute radical anarchism, many people say that the government is responsible for the Internet. But when asked why couldn't the Internet as we know it exist without a government, they give some incomprehensible word-salad. But Internet as we know it really relies on there being some sane government regulation. Without the government regulation, many ISPs would probably set up their DNS servers to respond to requests from all IP addresses, rather than just the IP addresses they are supposed to serve (because not filtering the IP addresses makes the server faster assuming there is no denial-of-service attack going on). That would make it trivial to implement large denial-of-service attacks. DNS servers often respond with huge responses to short queries, and hackers could simply spoof their IP address to flood the server they are attacking with DNS responses to queries it did not actually make. But people on Internet forums are usually not presenting that argument in a format that can be evaluated.

An example of a forum thread that leads to nowhere is "What do you think about gun control laws?". Discussing such things takes a lot of time, and you are not going to get any closer to the truth about whether the estimates about how many lives guns save per year (by Gary Kleck...) are pseudoscientific or scientific (which is probably a crucial question in any discussion about gun control laws). That's not to say a good forum question cannot touch religion or politics: it absolutely can touch religion, like my questions about the Vulgate (the Jerome's Latin translation of the Bible). The suggestion that Croatian word for wind should be spelt the same as the Serbian word for wind is spelt ("vetar") may also be considered politically sensitive. In the USA, perhaps even my question about special relativity might be considered politically sensitive by the right-wingers (some of whom consider special relativity to be a heresy). Good questions on Internet forums can also touch philosophy, particularly the history of philosophy, like my question about Descartes'es philosophy. But the difference between those questions and question about whether gun control is good should be obvious. Not even asking whether the Gary Kleck's estimate that guns save around 400'000 lives per year in the US is corroborated by any other study is likely to be productive (I received slightly more upvotes than downvotes on that question, but the answers I received were mostly completely irrelevant). Asking what some groups of people mean when they say the things they say sometimes works (like when I asked what gun control advocates mean when they say owning a gun makes you more likely to be a victim of a violent crime), but it usually doesn't work either (like when I asked what Christian Scientists mean when they say death is an illusion).

The only one of my questions that are somewhat related to telling apart science from pseudoscience that turned out to be liked by the community is the question "If calculating the p-value post-hoc is meaningless, why is it reasonable to believe the Grimm's Law (and other laws of historical phonology) is true?". Namely, in a discussion I had on the PhilosophicalVegan forum (I wouldn't recommend you to try to read all that, there isn't much interesting there), the moderator called brimstoneSalad claimed, among other things, that nothing about historical phonology can be known with "reasonable certainty" because it is against the scientific method to establish a function to calculate the p-value post-hoc. They also claimed that the methodology of historical phonology, such as discovering laws to explain the apparent exceptions to the most obvious rules (Verner's Law...) is "a how-to of pseudoscience". Well, I agree that there is an apparent contradiction between the claims "Establishing a function to calculate the p-value after the fact is meaningless." and "It is reasonable to believe the Grimm's Law is true.". But I think a lot better answer to that apparent contradiction is that "Establishing a function to calculate the p-value after the fact is meaningless." is not true. If what brimstoneSalad is saying were true, historical linguists would not be able to agree on anything (for the same reason astrologists aren't). brimstoneSalad had some responses as to how historical linguists are apparently capable on agreeing on quite a lot of things, which... I don't understand them, and I think they are word-salads. And I think that discussion made me understand what Richard Feynman meant when he said "Philosophy of science is as useful to the scientists as ornithology is to birds.", I guess Richard Feynman got stuck in such discussions and that those discussions made him say that (mistakenly thinking that those discussions are an actual philosophy of science). I was wondering what people who are actually educated in the philosophy of science think about that issue, so I asked it on the Philosophy StackExchange.

Of course, the fact that your questions get downvoted doesn't necessarily mean they are not well-researched. My question about whether anybody has done a study about whether deep orthography decreases the entropy of the written language (posted here, here and here) wasn't well-received, even though it is arguably more well-researched than my highly-upvoted questions about linguistics (I have done some actual measurements there, which I didn't do in my highly-upvoted questions). It seems as if, to people in soft sciences, the terms like "collision entropy" or even "p-value" sound like pseudoscientific buzzwords, which is very unfortunate. I have asked a question about that on Linguistics Meta StackExchange.

I am not sure what makes a good answer on an Internet forum. Here are some answers I have written that were well-accepted by the community, even though the reason for that escapes me (especially why my answer to "How do you say 'seagull' in Latin?" got so many upvotes):

UPDATE on 13/07/2025: The experience I had on Internet forums today really hurt my faith that the comparative historical linguistics is a significantly harder science than the study of the names of places. In Latin, there were two words meaning "tear (of an eye)": dacrima and lacrima. The word "lacrima" prevailed, and its descendants are the words for tears in modern Romance languages. And there were two words meaning "tongue (the body part)" and "language": dingua and lingua. The word lingua prevailed. That is called Sabine L, and is usually explained as initial 'd' changing to 'l' in some dialects of Latin. Now, if you ask linguists: "How do you know it is not precisely the opposite? What if 'lingua' and 'lacrima' were older forms?", they will respond with: "We have comparative evidence. The cognates to Latin 'lacrima'/'dacrima' are English 'tear' and Greek 'δᾰ́κρῠ', and a cognate to Latin 'lingua'/'dingua' is English 'tongue'. That's how we know the forms starting with 'd' are older.". But there is an obvious question here: If English tear comes from the same Indo-European root as lacrima, why is it not spelt something like *teighr? The 'k' in the middle of a word in Latin and Greek clearly corresponds to 'gh' in English, as in the number "eight" (compare Latin "octo" and Greek "ὀκτώ") and the word "night" (Latin "nox" and Greek "νῠ́ξ"), so why wouldn't it do that in the word "tear"? Well, I asked that question on Latin StackExchange, where it received two downvotes and was closed by the moderator. The reason? It's off-topic since the answer obviously lies in the English historical phonology, rather than in Latin or Greek. OK, let's ask that same question on English StackExchange. The result? They are pretending (in my opinion) to be unable to understand my question and have closed it. Why do people react to such questions that way? Is it because the contention that "tear" and "lacrima" are cognates is considered to be a "basic fact" and that therefore doubting it is considered unscientific and anti-intellectual? Are such supposed facts based on evidence or on nothing more than groupthink? You be the judge. One moderator of the Latin Language StackExchange agrees with me that this is a relatively good question and he suggested me to post it on Linguistics StackExchange. I did, but I am not at all sure that's the appropriate response. Cross-posting onto another StackExchange is almost never a good idea.

Wikipedia is the most reliable source of information on the Internet!

Wikipedia usually lets you hear both sides of the story about some issue and lets you make an informed oppinion. Other sources of information rarely do that. When Wikipedia is unreliable about something, then other tertiary sources of information (that is, those written by people who don't have very specialized knowledge of things they are writing about, such as encyclopedias or textbooks) are just as likely, if not even more likely, to be wrong about it.

UPDATE on 24/08/2023: To be fair, ever since I published my paper applying information theory to Croatian river names (you can read the English-language summary of it), and have tried to discuss it on Internet forums, my view on Wikipedia has changed significantly. I still think that what's on Wikipedia is very likely to be true, however, now I also think that reading too much tertiary sources of information (Wikipedia, etymological dictionaries...), and little-to-no primary and secondary sources of information, can and does give people a wrong idea how science works. To understand how science works, you also need to read primary and secondary sources, and not just tertiary sources. Tertiary sources almost never discuss p-values, which are the core principle of the modern scientific method. I think that many people I met on Internet forums are basically reading only tertiary sources of information, and that that is why "p-value" sounds like a pseudoscientific buzzword to them, and that that is why they reject my theories. It is unfortunate, but it shows why tertiary sources will not help you understand too much about how science works.

Given how common misunderstanding of statistics is in pseudosciences, a question is "How do you recognize when somebody is using statistics correctly?". I wish I knew the answer to that question. But my best guess is that it happens when somebody is calculating p-values and arriving at reasonable results. If somebody is not trying to calculate p-values, that can easily be because they do not understand statistics or don't like what statistics tells them (that their observations are likely to be due to chance). If somebody is, for example, arriving at a p-value of 1/10'000 in a very soft field (where you expect p-values to be something like 1/20), there is a very good chance they are calculating something incorrectly (like I was before I analyzed the problem of Croatian river names more deeply). There is a reason p-values are valued in science. Of course, there are exceptions. Ignaz Semmelweis, for example, was not calculating p-values, presumably because statistics back then was not yet advanced enough for that to be common or even possible. Or maybe because he thought the patterns he discovered were so obvious one does not need a p-value for that. Grimm's Law and Havlik's Law in linguistics are also so obvious once you look at the data that one does not need a p-value for them (though I am quite sure linguistics would go a lot further had it used statistics more). But I still think "Look for the p-values." is a good advice for telling apart science from pseudoscience.

Why would you expect larger p-values in softer fields? Well, you need to understand that, when you are doing historical phonology (Grimm's Law, Havlik's Law...), you are assuming that linguistic classification (whether some language is Indo-European or not) is correct. Linguistic classification is a harder field than historical phonology, the facts from linguistic classification are more certain than facts from historical phonology. That's why the p-values is historical phonology are larger than p-values in linguistic classification. And, when you are doing etymology, you are assuming both that historical phonology and that linguistic classification are correct. Thus, when doing etymology, you should expect larger p-values than if doing historical phonology. Etymology is a much softer field than historical phonology.

As an example of studies that are arriving at an unreasonable p-value (or not calculating the p-value at all), look at most studies about gun control. Most of the studies about gun control compare homicide rates in some city before and after some gun control law in that city was passed, and they conclude based on that whether it was effective or counter-productive. While that intuitively sounds like a reasonable methodology, it is not. Think of it this way: the vast majority of gun control laws only affect the sales of new guns. And there are 400 million guns already in the US. So, gun control laws only affect around 1% of total guns in existence. And homicide rates vary by around 6% from one year to the next. The signal-to-noise ratio is therefore at most 1:6. It is extremely unlikely that any such gun control study can arrive at a statistically significant result. The famous Gary Kleck's study where he tried to estimate the number of lives saved by defensive gun use each year at least does not suffer from that fatal flaw.

I think that many pseudosciences would cease to exist if Petzval Field Curvature were common knowledge. Namely, pseudoscientists often imply it is possible to see via a photograph whether some huge lines are parallel or straight. That's simply not how cameras work: the image that the lens produces is curved, while the light sensor in the camera is flat. Ironically, naked eye might be a better tool to tell whether some long line is straight or curved, as at least the retina of the eye is curved like the image that the lens produces. But schools, unfortunately, do not teach such things.

This should go without saying, but, in order for some observation to be evidence of the Earth being flat, it is not enough for it to be difficult to explain if you assume the Earth is round. It also needs to be easy to explain under the Flat Earth Theory. I think the only Flat-Earthers' argument that cannot be debunked simply by pointing out that obvious fact from epistemology is the argument "If the Sun were really 150'000'000 kilometers high in the sky, the crepuscular rays would seem parallel.", as it is indeed easier to suppose the Sun is only a few thousand miles up in the sky than to explain the optical illusion.

Or a less extreme example than Flat-Earthers, people who are denying global warming is anthropogenic. Mainstream climate science thinks that CO2 increase in the atmosphere causes a positive feedback loop of water increasing as well, increasing the effect of CO2 by around 3 times. People who are denying global warming is anthropogenic generally deny that that positive feedback loop exists. And most of their arguments are similar to this: "Almost all climate models which predict global warming also predict that infrared (long-wave) radiation from the Earth will decrease over time. Yet, the satellite data shows that it has increased."... without showing a mathematical model that predicts the Earth is warming and that infrared radiation is increasing. In other words, they are trying to replace mathematical models which at least explain why the Earth is warming with a mathematical model that doesn't even do that, just because they supposedly cannot explain infrared radiation increasing. That's going against the scientific method. And by the way, mainstream climate models aren't really predicting infrared radiation will decrease, they are predicting it will decrease slightly and then start increasing, and there were no satellites back when it was decreasing.

In case somebody is using such arguments, you can link him to my blog-post about not even wrong arguments.

An error that's common in pseudosciences that also belongs to misunderstanding epistemology is trying to use a soft science to contradict a hard one. How many times have you heard arguments such as "Saturated fat cannot cause heart disease, because our ancestors have been eating meat for millions of years, so we evolved against it." or "Fructose cannot be causing type-2-diabetes, as our ancestors have been eating bananas, which are full of fructose, for millions of years, so we evolved against it." or "Heme iron cannot be causing colon cancer, as our ancestors have been eating red meat for millions of years, so we evolved against it."? Such arguments are wrong on several levels. For the first two argtuments, we can refute them simply by pointing out the facts that meat of wild animals (rabits...) contains way less saturated fat than the meat we eat today, and that wild bananas contain way less fructose than bananas we eat today. All three of those arguments can be refuted by pointing out the fact that evolution doesn't care about diseases people tend to get when they are old, as life expectancy was significantly lower in pre-history than it is today. Also, what makes people who use those arguments think protection against those things even can evolve? But, more fundamentally, those arguments are attempting to use a soft science to contradict a hard one. Guesses about what our ancestors used to eat millions of years ago are way softer science than "Heme iron mixed with omega-6-acids in the presence of the enzymes found in human colon produces carcinogenous substances.". I also think Dubravka Ivšić, in her response to my paper about the river name Karašica, was also doing this error of attempting to use a soft science to contradict a hard one. Informatics is a way harder science than historical linguistics, and, if informatics says that the probability for the k-r pattern in Croatian river names to emerge by chance is negligible, you contradict that using either informatics or some even harder science, not historical linguistics. You don't get to use magical languages to get around the limits put by informatics.Another such example is the common claim, often made by

anti-vegetarians, but also by some environmentalists, that methane in

the atmosphere mostly comes from methane we use as natural gas. Just

eye-balling the data makes it obvious that explanation is false.

Methane emissions reached their peak somewhere in the 1980s, and

reached record low in 2003, and is now only slightly above the 2003

levels. Clearly not correlated with the amount of methane we use: we

are using more and more methane, mostly because we are switching from

coal to natural gas as it is cleaner. The hypothesis that a

significant percentage of our methane emissions come from grass-fed

cows is at least not as blatantly contradicted by the data.

(UPDATE: I stand corrected: due to some intriguing technical details,

eye-balling the data to estimate how our methane emissions changed

over time doesn't really work. I've made

a YouTube video explaining why. In case you cannot open it, try downloading

this MP4.) I suppose people say stuff like that because human brain is wired to

be against empiricism and to embrace the flawed philosophy of

rationalism. Empiricism makes people humble, rationalism does not. Or

maybe they are just being intellectually lazy and unwilling to look at

the actual data.

I think the only situation in which it makes some degree of sense to be a conspiracy theorist is if you are a ruler of a totalitarian society, so that you suppose there is something that's being hidden from you specifically. During the Great Chinese Famine, in late 1958, Mao went to Henan to investigate the reports of massive crop failure. However, the officials there somehow came to know exactly which places he is going to visit, and they replanted rice from multiple acres into one to hide that the crops have failed. In that case, Mao would come to the right conclusion had he been a conspiracy theorist. Similarly, the Crimean politician called Potemkin famously built fake villages full of houses with nice facades to hide the poverty that people were living in from the Russian empress Catherine II in 1787. In that case, Catherine II should have supposed that there is a medium-size conspiracy to hide something from her.

UPDATE on 22/09/2019: I've just posted a YouTube video about pseudoscience in American politics. If you can't open it, you can perhaps try to open a low-quality MP4 file hosted on this server (it can be opened on almost any platform using VLC Media Player). Failing to do even that, you can probably download the MP3 audio.

UPDATE on 08/03/2020: I've just posted a YouTube video criticising climate change denialism, you can see it here. If you can't open it, try this.

UPDATE on 19/04/2020: Here is the Croatian version of my parody of the conspiracy theorists. If you can't open it, try the DOC, DOCX and ODT.

UPDATE on 07/04/2022: I have made a video debunking Tony Heller's claims about the election fraud. However, YouTube refuses to let me upload it there, so I have uploaded it on GitHub Pages. My best guess as to why it cannot be uploaded is that YouTube's Artificial Intelligence thinks I am claiming the election fraud. Nothing could be further from the truth, I am critical of claiming such a thing. But that's how censorship using artificial intelligence works.

UPDATE on 01/12/2023: A blogger called dr. Moran has made a video claiming that Moderna vaccination somehow magically (he doesn't even provide a speculative explanation of how it could) causes myocarditis in 3% of vaccinated adolescents (that is, around 20 to 50 times more often than COVID-19 does). I made a video response to that video. In case you cannot open it, try downloading this MP4 and opening it in VLC or some similar program. In all seriousness, though, making response videos to such claims is probably a waste of time. I think that Flat-Earthism has more chance of catching on that that does.

UPDATE on 18/07/2025: I've written a blog-post about using computer simulations in social sciences.

UPDATE on 04/02/2024: I have made a video refuting the Flat-Earth theory as a former Flat-Earther. In case your browser cannot open it, download this MP4 and open it in VLC or something similar. And please spread the word, Flat-Earthers need to be woken up.

UPDATE on 03/10/2021: I have received some criticism on Internet forums that this text appears to be intended to slam everybody else as pseudoscience except me, and that it is what pseudoscientists do. That was not my intention at all, my intention was to make you more skeptical of all things outside the mainstream, including me. As well as the ideas you come up with that contradict the mainstream science. Outside of scientific consensus, no idea is anything more than possibly right. I, for example, think my idea about collision entropy of different parts of the grammar being measurable and useful to prove some etymologies of names of places in Croatia (you can read an English-language summary on my blog) has enough probability to be right to be worth sharing, and that it is at least interesting even if it is not correct. I am quite certain that, even if I am misunderstanding statistics here, my misunderstanding is not nearly as severe as that of anti-vaxxers or typical pseudolinguists. To judge whether it is correct, use your brain, you are probably more objective than I am. But also have a bit of self-doubt and realize there are people who know far more than you do about the subject, and who are far more likely to be right. Understand also that it is sometimes hard to tell who is an expert in some field (physicians, for example, know about nutritional science only slightly more than an average person), or even if anybody has meaningful expertise about the topic (for example, what happens if we try to radically transform the society to deal with climate change or a pandemic). And try to make sure you are hearing both sides of the story, and not just one which is easier to read (which is usually pseudoscience). (UPDATE on 04/09/2025: Anyway, it seems to me that I was doing an error in my calculations, not so much because of misunderstanding statistics, but because of ignoring linguistic typology and cross-linguistic phonology. Namely, I implicitly made the assumption in my calculation that the collision entropy of the pairs of consonants is approximately-evenly distributed among the pairs of consonants in a word. That is approximately true for languages such as Hawaiian, with very restrictive phonotactics, but is not remotely true for languages such as English or Croatian. English and Croatian allow for many consonant clusters at the beginning and at the end of the word, and those consonant clusters are governed to a large extent by the Law of Sonority, also known as Sonority Sequencing Principle. The Law of Sonority effectively, in languages with lenient phonotactics such as English or Croatian, decreases the collision entropy of word-initial and word-final consonant pairs by around 1 bit. That makes my calculations wildly off. For example, the upper bound of the p-value of the k-r pattern in the Croatian river names is not 1/17, but is around 85%. You can read more about it on my blog-post about leaving cults. Two things are really amazing to me from this story. One is that the biggest problem by my calculation wasn't noticed by some expert in Croatian toponyms, with whom I was discussing my paper for three long years, but by some Semitic languages expert on Discord. And the second thing that's amazing to me is that it took me nine years to realize what is obvious to most laymen: that there is no good way to scientifically study ancient toponyms. It took me 5 years of studying toponyms to realize that the mainstream methodology, the Mayer's one, does not even work on paper, and it took me 4 more years of studying to realize that the main opposing methodology, the Krahe's one, works on paper but not in reality. It is not obvious to me, as a computer engineer, what would be the mathematical justification for the Mayer's methodology, and the Krahe's methodology appears to be justified by basic information theory, but, once you look more into it, you see that natural languages do not really behave the way basic information theory predicts. How it is that many people were able to see that a lot sooner than I was? It's not as if the study of the toponyms involves a conspiracy theory or is based on endless not-even-wrong arguments, and the lack of significant scientific consensus, while real in the study of the toponyms, is not at all obvious at the first sight. And the ad-hoc hypotheses, if existent in the study of toponyms, are not at all blatant. I fail to see why the study of the toponyms would be ad-hoc if chemistry is not ad-hoc, for example. Many people are saying "Math - that's the difference between science and bullshit.", but the study of the toponyms is not a completely math-free field. Especially not my paper in which my main argument was that basic information theory suggests that the p-value of a certain pattern in the Croatian river names is between 1/300 and 1/17. Furthermore, it seems undeniable to me that people, with the possible exception of my professors at the university, were more skeptical of my work the more math I used in my arguments, rather than becoming less skeptical. So, how were so many people capable of almost-immediately realizing that's bullshit? I'd love to hear your thoughts.)

Content

- What is pseudoscience?

- SCIgen - people attribute apparent incoherence to their own lack of knowledge

- Why many people follow pseudoscience rather than science?

- What makes sense to scientists is different from what makes sense to laymen

- Why school knowledge does not help us recognize pseudoscience?

- Why censorship is not a good answer to pseudoscience?

- Ad-hoc hypotheses - what are they and why they are distinctive of pseudoscience

- Why is there a lot of consensus in science, but little in pseudoscience?

- Why demanding more rigorous experiments, but never doing ones, is distinctive of pseudoscience?

- Why Internet forums are not a way to detect pseudoscience

- Some myths about pseudoscience

- Why common knowledge is unreliable

- How pseudosciences come to be?

- Three common sources of errors in pseudosciences

- Conspiracy theories

- Conclusion

What is pseudoscience?

Richard Dawkins once said: "For many people, science is yet another belief system, as valid as any other. But, actually, it isn't so: airplanes really fly, flying carpets do not. There is something special about science. Which is why, unlike other belief systems, science is worth trying to understand it and following it.".Pseudoscience simply means "false science", something which is presented as science, but demonstrably doesn't follow the methods of science. Many people believe that pseudoscience is basically isolated to specific and widely discredited fields, like astrology and numerology. However, I would argue that pseudoscience is probably everywhere,

Do you know how,

for example,

the mathematicians

know the Pythagorean

Theorem is correct?

In school,

we aren't taught

how scientists

know what they know.

SCIgen - people attribute apparent incoherence to their own lack of knowledge

To understand why, consider the case of SCIgen. It's a computer program that generates nonsense in the form of texts about informatics, using the vocabulary typical for them. Those texts were sent to a few well-known peer-reviewed journals. Most of them rejected them, yet some of them accepted them. When asked why, one of the recensents responded that it didn't make sense to him either, but he attributed its apparent incoherence to his own lack of knowledge in that particular field of informatics (Here is a paper I've recently written about informatics, I can understand how somebody might have a hard time differentiating stuff like that from gibberish. As well, like I've written in my blog-post about informatics, my father thought that I was teasing him when I told him I have a course at the university called "object-oriented programming", and I can kind of see why he would think that.).Pseudosciences are widespread because of the way people react to nonsense: they ascribe the apparent incoherence to their own lack of knowledge. And more intelligent you are, more likely you are to fall into that trap, because, more intelligent somebody is, easier it is for him to imagine that there is something he is unaware of, so that something that doesn't make sense to him actually does make sense. This type of thinking is as flawed as it can get, but it's very common (and perhaps mostly subconscious).

Why many people follow pseudoscience rather than science?

In fact, I would argue there are reasons why intelligent but ignorant people are sometimes more likely to believe pseudoscience than actual science. First, pseudoscientists usually have more exciting ideas than actual science does. For example, pseudoscientists often claim to have discovered a method to reliably tell if somebody is lying to you. Those things interest people. Psychologists arguing such methods can't work much better than chance? Not so much. Pseudoscientists often claim they've reconstructed the first human language. Many people find that exciting. They will rather read that than read the linguists explaining their methods are contrary to the methods accepted in linguistics (that their methods, if applied to rigorously studied language families such as Indo-European languages, would lead to a huge number of false positives and also to many false negatives). Second, pseudoscientists usually have shorter rhetorics than the actual science does. For example, pseudoscientists often say things such as that the double-slit experiment proves that bilocation is possible or that the quantum entanglement explains the telekinesis. Now, if people actually read both sides of the story, that is, both what the pseudoscientists write and the actual science of the double-slits experiment and quantum entanglement, they would ask what drugs those pseudoscientists are on. But most of the people don't do that. They think that if someone has a short rhetoric regarding something, he knows what he is talking about.What makes sense to scientists is different from what makes sense to laymen

Third, though I am not sure if that plays a significant role, sometimes what makes sense to a scientist is different from what makes sense to a layman. To understand why, consider the following statements:- The ice will melt sooner on a piece of wood than on a piece of metal of the same temperature, because the metal feels colder when you touch it.

- The horizon appears to rise with you as you climb, and, if the Earth were round, we would expect it to fall. Therefore, the Earth is flat.

- The name of the Croatian village Vîljevo (pronounced VEEL-yev-aw) obviously comes from the Latin word vīlla (country house), both the consonants and the vowels and the accent match.

The second statement is false, because, well, the basic trigonometry. First of all, if the Earth were flat, I hope you agree, there would be no horizon in the first place for us to make this observation. Therefore, simply yelling that the Earth is flat isn't an explanation at all. Of course, those who claim the Earth is flat will claim there is some basically undetectable (for whatever reason) curving of light upwards, and that also can't be considered an explanation.

A diagram explaining

why the horizon

appearing to rise

as we climb doesn't

prove the Earth

is flat

, where r is the radius of the Earth (around 6'000'000 meters)

and h is your height relative to the surface of the Earth. So, if

you are on the Mount Everest (9'000 meters height), you will see the

horizon at the angle of 3.14 degrees. Barely perceptible. Actually, it's

not even barely perceptible, because, when you are on the Mount Everest,

the mountains hide the horizon in the first place. Furthermore, some

optical illusions make it clear that what our brain perceives to be eye

level, or even what it perceives to be a horizontal level at all, is

determined not only by the equilibrium sense in our ears, but also by

visual clues. This is well-known to mountain cyclists as the false flat

illusion. That makes the difference between eye level and the horizon

even more difficult to perceive. The fact that the horizon is not always

at your eye level, however, can be seen in at least two ways. You can

see it indirectly by watching the sunset sitting down and then quickly

standing up (the sun stays at your eye level as you stand up, but the

horizon falls slightly). And you can also see it directly using a device

with a gyroscope and a camera (such as modern smartphones). I think the

fact that the horizon demonstrably falls as you climb is a good argument

against the Earth being flat, you can see on

this forum thread

whether it works.

, where r is the radius of the Earth (around 6'000'000 meters)

and h is your height relative to the surface of the Earth. So, if

you are on the Mount Everest (9'000 meters height), you will see the

horizon at the angle of 3.14 degrees. Barely perceptible. Actually, it's

not even barely perceptible, because, when you are on the Mount Everest,

the mountains hide the horizon in the first place. Furthermore, some

optical illusions make it clear that what our brain perceives to be eye

level, or even what it perceives to be a horizontal level at all, is

determined not only by the equilibrium sense in our ears, but also by

visual clues. This is well-known to mountain cyclists as the false flat

illusion. That makes the difference between eye level and the horizon

even more difficult to perceive. The fact that the horizon is not always

at your eye level, however, can be seen in at least two ways. You can

see it indirectly by watching the sunset sitting down and then quickly

standing up (the sun stays at your eye level as you stand up, but the

horizon falls slightly). And you can also see it directly using a device

with a gyroscope and a camera (such as modern smartphones). I think the

fact that the horizon demonstrably falls as you climb is a good argument

against the Earth being flat, you can see on

this forum thread

whether it works.The third statement is wrong, because, well, the word *vīlla (with a long 'i'), borrowed into Old Croatian, would give something like *Bȁo (with a short falling tone on 'a') in Modern Croatian. Even if a linguist doesn't know the sound changes that happened between Old Croatian and Modern Croatian, he still wouldn't have expected the word to remain unchanged for more than a thousand years. The consonants, the vowels and the accent "matching perfectly" (ignoring the sound changes that have occured) is a strong (though not a necessary) argument for the words being unrelated, rather than related, because the sound changes don't affect individual words, but whole languages. A failure of a sound change to affect a word it could have affected is what requires an explanation, and not the word changing to the unrecognizability due to the regular sound changes. A good response to somebody who is suggesting such etymologies on an Internet forum might be something along the lines of:

Look at the transliterated, but not translated, text of the

Baška Tablet. How many letters do you have to add, remove, or

change in order to get modern Croatian? The toponyms borrowed from

Latin passed through that same filter. In fact, an even more

complicated filter, because, by the time the Baška Tablet was

written, the monophthongization of the Proto-Slavic diphthongs already

occurred, and so did the change from 'a' to 'o', and the toponyms

borrowed from Latin were also affected by sound changes that had

occurred in the dialect of Latin that was spoken in modern-day Croatia

in the 7th century. Do you understand now why your etymology, which

supposes that a toponym remained unchanged for 2'000 years, is very

unlikely?

And I think one of the reasons why my etymology that Karašica

comes from Illyrian *Kurr-urr-issia (to flow-water-suffix) isn't getting

accepted is because many people who study Croatian toponyms,

unfortunately, aren't aware of the historical phonology, and don't

understand that *Kurrurrissia would be borrowed as

*Kъrъrьsьja into Proto-Slavic, which would

regularly give *Karrasja after the Havlik's Law and would regularly give

*Karaš- after the loss of geminates and the yotation. I can see

why, to somebody who is ignorant of historical phonology, the

widely-cited etymology that Karašica comes from Turkic *kara-sub

(black water) would seem more plausible, even though *karasub would be

borrowed as *Korosъba into Proto-Slavic, which would give

*Korozba in modern Croatian. Alongside the ignorance of information

theory which says that the k-r pattern in the Croatian river names is

very unlikely to be a coincidence.The point is, it's very easy for a layman to convince himself those statements (and the similar ones) make sense, sometimes even easier than it is to understand the true science to the point when it actually makes sense. Our senses are unreliable. We witness illusions and hallucinations (at least the ones such as dreams) all the time. Even when they do give us correct information, it's very easy to misinterpret. The science seeks to correct those things. Pseudoscientists sometimes appear to exploit those things to make people believe absurdities.

Why school knowledge does not help us recognize pseudoscience?

So, what do I think, what's a good way of recognizing pseudosciences? Well, let me be clear: the knowledge we are taught at school helps very little, if at all. We usually aren't taught how scientists know what they know, and that, during the history of science, most of the supposed discoveries were actually false.How history of science taught at school makes people susceptible to survivorship bias